Written by Rupert GL

We always knew the Narathiwat expedition was going to be tough. Thailand’s Deep South is never an easy place to go. In previous years, the seemingly unsolvable insurgency which sought to render the region ungovernable had stifled the ambitions of any naturalist dreaming of uncovering the secrets of the Deep South. However, as the violence slowly subsided over the years, the militarised police checkpoints now lying largely unmanned, and curfews (both Covid and military) gone, it seemed like the time had come to embark on the long-anticipated expedition to Narathiwat. Visions of virgin Malayan mixed-dipterocarp forests and their colourful canopies called to us, shrouding ambitions of finding snakes so rare that you could count their records on one hand.

We had 3 major targets for the trip, all of which we felt were bordering on unrealistic. The number one target for us was Wirot’s pit-viper (Craspedocephalus wiroti), a very unique viper with eye-watering rarity. Despite historic records from several places across southern Peninsula Thailand, Narathiwat seems to be the only remaining province with a known population. Second was the blue coral snake (Calliophis bivirgata flaviceps). This species needs no introduction, it is one of the most sought-after species throughout its range. In Thailand, it is particularly scarce, almost never sighted by herpers. By far the most records come from Thailand’s deep south, so if we were ever going to find one, it was going to be here. Third on the list of top targets was the Sumatran pit-viper (Trimeresurus sumatranus). For the longest time, this species was only fabled as still occurring in Thailand through the blurry smartphone images of park rangers in Narathiwat. That was until David, myself, and some friends of ours found a juvenile in Narathiwat in 2019. The only reason this was not top of the list is because we had seen this species here already - but finding an adult T. sumatranus would be the most incredible find of them all.

This expedition was guaranteed to be exhausting and challenging, so it was important that everyone partaking was mentally prepared, as well as experienced.

As the drive from where we are based to Narathiwat is a 15-hour slog on the best of days, we decided to split the drive up with a layover in a familiar location in the southern peninsula. We left home at midnight and drove overnight, arriving in what should have been the early morning sun. That was not the case, however, as we arrived to gloomy clouds and incessant downpours. Rain in Thailand typically lasts a couple hours and subsides, so we slept until the early afternoon, expecting to wake up to birds chirping and the sawing of cicadas. We woke up to even heavier rain, and it did not abate for more than a few minutes all afternoon.

Nightfall came and the rain continued to relentlessly pound the restaurant rooftop, foreboding sodden clothes, equipment, and spirits in regards to the night ahead. Yet, as we arrived back at our accommodation, it reduced to a light drizzle. This was the excuse we had been waiting for, so we grabbed our gear at record speed and hit the forest.

The first snake of the night was an Indo-Chinese rat snake (Ptyas korros) which Harry found resting in a small shrub right beside where I parked the car. Meanwhile, David discovered this wonderful jasper cat snake (Boiga jaspidea), what most consider to be the rarest Boiga in Thailand, a lifer for both David and Harry, and the final Boiga species which David had to see in Thailand.

Indo-chinese rat snake (Ptyas korros)

Jasper cat snake (Boiga jaspidea)

The night was relatively slow for a couple hours following these quick-fire finds, the only snakes seen being a grey morph juvenile Asian vine snake (Ahaetulla prasina) and its dipterocarp-forest dwelling congener, the Malayan vine snake (Ahaetulla mycterizans).

Oriental vine snake (Ahaetulla prasina)

Malayan vine snake (Ahaetulla mycterizans)

As the typical cave we visit in this area was flooded to the roof, I made an inspired decision to check out a small road which I suspected to lead to a cave not labelled on Google Maps or Earth. The cave itself was too flooded for herping, but we saw a pretty juvenile Cyrtodactylus lekaguli and Moon spotted a large and beautiful Ridley’s cave racer (Elaphe taeniura ridleyi) in a limestone crevice.

Lekagul's bent-toed gecko (Cyrtodactylus lekaguli)

Ridley's cave racer (Elaphe taeniura ridleyi)

Soon after, the miraculous cessation of rain came to an end and the downpours began yet again. Already soaked from head to toe, and not satisfied with taking an early night, Harry and I waded back out into the waterlogged lowland forest in search of more snakes. Not long into the walk, I spotted a huge western mangrove cat snake (Boiga melanota) being washed downstream in a strong current. Minutes later, Harry caught a fantastic melanistic (speckled morph) dog-toothed cat snake (Boiga cynodon), also measuring around 2 meters long (although 2 meters is borderline diminutive for this gentle giant).

Western mangrove cat snake (Boiga melanota)

Melanistic dog-toothed cat snake (Boiga cynodon)

Continuing through the flooded trails, I spotted another Ahaetulla mycterizans and an elegant bronzeback (Dendrelaphis formosus) resting on branches in the same small clearing. Due to the rain, we didn’t bother with anything other than handheld record shots of the D. formosus. At this point, it was getting unacceptably late and we were waking up early to drive to Narathiwat the next day, so we decided to call it a night here.

Elegant bronzeback (Dendrelaphis formosus)

4AM is an early night?

However, I spotted a cute little blunt-headed slug snake (Aplopeltura boa) on the walk back, and David found a juvenile Malayan pit-viper (Calloselasma rhodostoma) right outside the door of our accommodation - the first time I’d ever seen this species in the area despite several trips here throughout the years.

Blunt-headed slug snake (Aplopeltura boa)

Malayan pit-viper (Calloselasma rhodostoma)

After a rather productive night at our layover location, it was time to get to the meat and bones of this expedition - Narathiwat. Alas, as old issues wane, new problems arise.

I had carefully planned our 2022 Herping Expeditions around seasonality. While the dry season of January-April typically puts a very un-literal dampener on snake activity in most parts of Thailand, the southern peninsula remains highly productive even in the driest times of year. Therefore, focusing attention on the south while the rest of the country undergoes a slow spell was elementary. What I didn’t plan for was for the southern peninsula to be experiencing unseasonal rainfall of unprecedented proportions. Small trickling streams had turned into torrents and rivers had burst their banks, turning vast swathes of lowland into a murky lake. Houses and roads were lost beneath the dark waters, leaving many trapped, destitute, or worse. For us, it meant that what should have been a 6-hour drive from our layover location became a 9+ hour slog of stress, where at many points we questioned if we would even make it to our dream destination. Additionally, in an almost comedic turn of events, the accommodation which we had pinned our hopes on called us to tell us they had *no water* and it may not be fixed for days. However, after gingerly traversing roads-turned-rivers, taking huge detours to avoid lost bridges and flooded dales, and being accosted by police who thought we’d illegally entered from Malaysia, we made it to Narathiwat.

This road-turned-river increased our stress levels significantly

Once checked into our backup accommodation and prepared for the night, we were faced with more daunting flooding-related prospects. Firstly, whether our selected herping spots would be accessible, and secondly, whether we would become trapped here if the flooding continued. We already considered ourselves lucky that the flooded roads outside Waeng town were shallow enough for my slightly lifted Honda CR-V to cross, but continued rain could rapidly make these exits impassable. Safety was also forced to the forefront of our minds, as we had driven past a collapsed bridge which had brought a car into the river below, leading to the passing of all 7 people in the vehicle. There were fresh landslides and fallen trees everywhere - very dangerous circumstances to be driving in.

This particular landslide tested the car and our resolve

Fortunately, the forecast looked favourable for the following days (only 90% or 80% precipitation as opposed to 100%), and the rain had eased off. Moreover, we found a route to our herping location which avoided significant flooding. Thus, charged with exhilaration and anticipation, we embarked on the first night of the expedition proper.

It was over an hour’s drive to the first site from our backup accommodation, so before even reaching the forest, we road cruised two sunbeam snakes (Xenopeltis unicolor) and one Hypsiscopus cf. plumbea.

Sunbeam snake (Xenopeltis unicolor)

Plumbeous water snake (Hypsiscopus cf. plumbea)

Once arrived and out in the forest, we encountered more challenges. Trails had been turned into muddy streams, slopes were saturated and collapsing beneath our feet, and actual streams were impassable or impossible to walk along due to the strong currents. The terrain was treacherous, made worse by an endless army of leaches marching towards our ankles from every angle. By the end of the first night, I had leach bites on my forehead, neck, chest, and ankles. As if things couldn’t get any more unwelcoming, there was an abundance of night hornets (Provespa anomala) being attracted to our torchlights, and Harry was unfortunate enough to be stung on the neck by one. Bad terrain, leaches, and wasps didn’t matter to us though, as we had made it to the forest we’d fantasised about for many years, and it was time to find some snakes.

Tiger leeches planning their dastardly attack

Leech damage

The night began with not one, but 4 Hagen’s pit-vipers (Trimeresurus hageni), clearly the dominant Crotalinae in the area. Cyrtodactylus quadrivirgatus geckos were also highly abundant.

Hagen's pit-viper (Trimeresurus hageni)

Four-striped gecko (Cyrtodactylus quadrivirgatus)

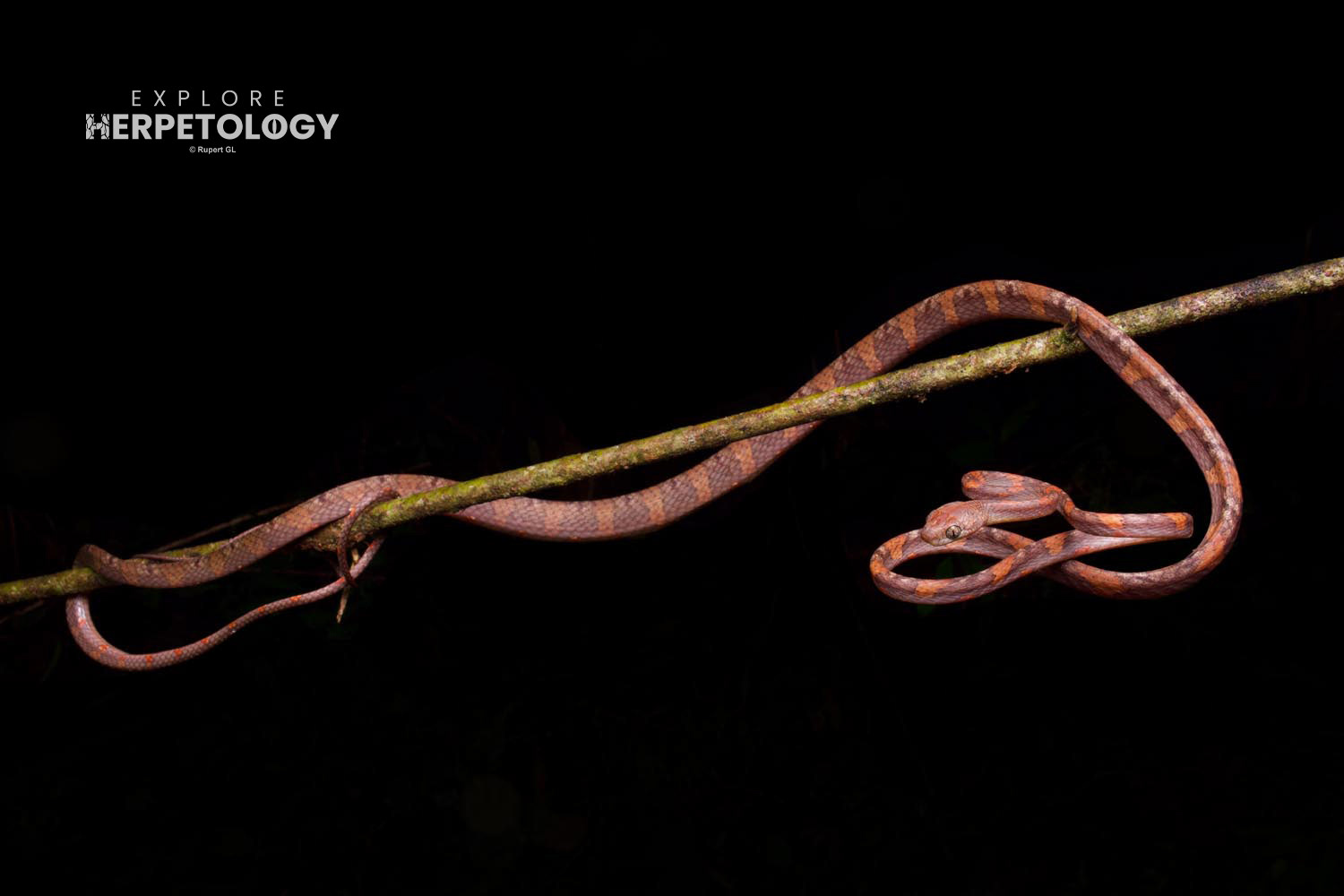

We added another Boiga to the species count with a large white-spotted cat snake (Boiga drapiezii), an exceptionally slender species. Later, I jumped off Harry's shoulders in order to retrieve a young female Wagler’s pit-viper (Tropidolaemus wagleri), not always a common species in this part of Narathiwat. The last snake hiked in the forest was yet another Jasper cat snake (Boiga jaspidea). We shot some quick video for David’s YouTube Channel and quickly released due to the return of heavy rain.

White-spotted cat snake (Boiga drapiezii)

Young female Wagler's pit-viper (Tropidolaemus wagleri)

Jasper cat snake (Boiga jaspidea)

We had only made it into the forest after 11pm, and it was past 4am at this point, so we decided to return home. On the drive back, we found another Hypsiscopus cf. plumbea and a Pareas margaritophorus agg. (neither photographed) on the road.

In the morning of our second day in Narathiwat, we got a call from our original accommodation informing us that they had indeed fixed the water and we could now check in - a huge relief. Before leaving the old guesthouse, I spotted a long-tailed sun skink (Eutropis longicaudata) in the garden, a patchily distributed species I’d only seen once before in Thailand. Upon arriving at our new homestay, Harry flipped a Siamese supple skink (Lygosoma cf. siamensis) in the yard. Both these backyard lizards represent significant range extensions.

Long-tailed sun skink (Eutropis longicaudata)

Siamese supple-skink (Lygosoma cf. siamensis)

We got into the forest at a more reasonable time this evening, quickly finding two subadult Bengkulu cat snakes (Boiga bengkuluensis). I was surprised we hadn’t found this species yet, considering that it is one of the most common Boiga in Southern Thailand. We also caught a large Peter’s bent-toed gecko (Cyrtodactylus consobrinus).

Bengkulu cat snake (Boiga bengkuluensis)

Bengkulu cat snake (Boiga bengkuluensis)

Peter's bent-toed gecko (Cyrtodactylus consobrinus)

The trails weren’t as productive as they were the night before, so we got in the car to check out a different spot. En-route, we road cruised a large Malayan banded wolf snake (Lycodon subcinctus) and a white-spotted slug snake (Pareas margaritophorus).

Malayan banded wolf snake (Lycodon subcinctus)

White-spotted slug snake (Pareas margaritophorus agg.)

In line with the slow nature of this night, it took us a long time to find our 5th snake of the night, but it was worth the wait. Species-wise, not a great find, but this Hagen’s pit-viper (Trimeresurus hageni) eating a four-lined tree frog (Polypedates leucomystax) was an awesome observation.

Hagen's pit-viper (Trimeresurus hageni) predating a four-lined tree frog (Polypedates leucomystax)

Hagen's pit-viper (Trimeresurus hageni) predating a four-lined tree frog (Polypedates leucomystax)

The only further snake sightings that night were juveniles of both Trimeresurus hageni and Boiga bengkuluensis, as well as the first keeled slug snake (Pareas carinatus ssp. carinatus) of the trip. However, we did see a very nice Johor flying frog (Zhangixalus prominanus) and some pools of breeding Ingerophrynus parvus.

Bengkulu cat snake (Boiga bengkuluensis)

Keeled slug snake (Pareas carinatus)

Johor flying frog (Zhangixalus prominanus)

Lesser toad (Ingerophrynus parvus)

After 2 nights and no notable observations, we decided to switch up our strategy and hit the forest harder than ever. Don’t get me wrong, it was still raining on and off throughout each day without more than a fleeting slither of sunshine, but we could focus more on walking streams now that the daily rainfall had reduced and the rushing water had receded, leaving rocky banks more manageable. The previous 2 nights had focused on the lower elevations where there had been confirmed records of Craspedocephalus wiroti, whereas tonight we’d be focusing more on Trimeresurus sumatranus, for which we believed lower mid-hill forest was better. Before even reaching the streams, we found a large Hagen’s pit-viper (Trimeresurus hageni).

An example of the forest streams we would hike each night

Hagen's pit-viper (Trimeresurus hageni)

We hiked low hill forest streams for many hours, enduring steep slopes, slippery rocks, and innumerable leaches, but found many snakes in the process. The first Malayan krait (Bungarus candidus agg.) of the trip was a cool find, along with the first triangle keelback (Xenochrophis trianguligerus).

Malayan krait (Bungarus candidus agg.)

Triangle keelback (Xenochrophis trianguligerus)

There were also several repeat species, including an impressive third Jasper cat snake (Boiga jaspidea), a white-spotted cat snake (Boiga drapiezii), an elegant bronzeback (Dendrelaphis formosus), as well as 2 keeled slug snakes (Pareas carinatus), a Boiga bengkuluensis, and a small Ahaetulla mycterizans.

Jasper cat snake (Boiga jaspidea)

White-spotted cat snake (Boiga drapiezii)

Malayan vine snake (Ahaetulla mycterizans)

Elegant bronzeback (Dendrelaphis formosus)

Keeled slug snake (Pareas carinatus)

We split up and lost each other several times in this process, but David, Moon, and I reconvened to hike a stream at the higher elevations - near where we found our Trimeresurus sumatranus in 2019. Shortly into our search, I spotted the first notable snake from our time in Narathiwat, a Schlegel’s reed snake (Calamaria schlegeli) moving through the leaf litter. This species can only be found in Thailand’s Deep South.

Schlegel's reed snake (Calamaria schlegeli)

Not long after, we got a huge (3 meter) white-bellied rat snake (Ptyas fusca) resting in a tree, followed closely by a blunt-headed slug snake (Aplopeltura boa), as well as a very pretty Cyrtodactylus bintangrendah.

White-bellied rat snake (Ptyas fusca)

Blunt-headed slug snake (Aplopeltura boa)

Bintangrendah bent-toed gecko (Cyrtodactylus bintangrendah)

Once back to the road, it was getting seriously late. However, I insisted that we should make a stop at one more stream before calling it for the night. Harry quickly found a juvenile Trimeresurus hageni, and I found a Brown’s wolf gecko (Gekko (Luperosaurus) browni), a species with no published records from Thailand.

Hagen's pit-viper (Trimeresurus hageni)

Brown's wolf gecko (Gekko browni)

As I was retrieving my camera gear to take pictures of this particularly fascinating gecko (which David commented looks like CatDog from the cartoon), I heard Harry screaming in joy from across the stream. With the gecko in hand, I, along with David, began sprinting towards the origin of the call. As we got closer, the words became clearer over the rushing water and I could clearly make out “SUMATRANUS!”.

Indeed, completely unbelievably, we had successfully managed to find *another* Sumatran pit viper (Trimeresurus sumatranus) in Thailand, a feat which countless others have tried tirelessly for, and failed. This time we had found an adult male, which made the feat even more incredible. This certified showstopper officially ended what was, in retrospect, the most productive night of the trip in terms of numbers of snakes.

Sumatran pit-viper (Trimeresurus sumatranus)

An amazing snake and a very happy man

Sumatran pit-viper (Trimeresurus sumatranus)

Riding high off the first sensational find of the trip, I decided to take the group to check out a new (nearby) site. It was a degraded area with a lot more footfall (including poachers) than the places we’d been searching the previous nights, so expectations were not high. However, minutes into the trail, I spotted a rusty-barred kukri snake (Oligodon signatus) in the roots of some vegetation. This rare species was one of our key colubrid targets, only occurring in Thailand’s Deep South.

Rusty-barred kukri snake (Oligodon signatus)

The trail uncovered a further 3 snakes, but all species we’d seen before. First was another blunt-headed slug snake (Aplopeltura boa), a species which is supposed to be uncommon (I suppose the rain brought them out in force), a sunbeam snake (Xenopeltis unicolor), and the (at this point) ubiquitous Trimeresurus hageni.

Blunt-headed slug snake (Aplopeltura boa)

Sunbeam snake (Xenopeltis unicolor)

Hagen's pit-viper (Trimeresurus hageni)

Afterwards, we decided to do an hour-long drive to another new site. This site turned out to be a bust - nowhere to walk around - but the 2 hours of driving wasn’t a complete waste. We started by road cruising a Malayan racer (Coelognathus flavolineatus), a new one for David and Harry, and always a lovely snake to see for me. On top of this, we found a white-spotted slug snake (Pareas margaritophorus), an adult Malayan banded wolf snake (Lycodon subcinctus), and 3 sunbeam snakes (Xenopeltis unicolor) on the road, one of which was a subadult with a nice pinkish-white head.

Malayan racer (Coelognathus flavolineatus)

Malayan banded wolf snake (Lycodon subcinctus)

Juvenile sunbeam snake (Xenopeltis unicolor)

Not content with the night’s findings so far, we hit one of the regular trails at 3am to look for Craspedocephalus wiroti, and while inspecting a large dead tree, I discovered a dusky/slender wolf snake (Lycodon albofuscus) hunting beneath the bark. It may be hard to tell from photos, but this species is long, immensely slender, and has extremely keeled scales, feeling highly unlike most other snakes in the region. This very uncommon species was one of the team’s favourite colubrid finds from this trip.

Slender wolf snake (Lycodon albofuscus)

Heavily keeled scales of Lycodon albofuscus

The last snake of the night was another massive white-bellied rat snake (Ptyas fusca) which Harry spotted sleeping above a stream, although I had hurt my back at this point so didn’t take much interest.

White-bellied rat snake (Ptyas fusca)

Our 5th night in Narathiwat was supposed to be the last at this location (we were planning to scout out some swamp forest the following night), so it was crunch time to find Wirot’s pit-viper (Craspedocephalus wiroti), our number 1 target. Despite several great finds, I had still not seen a single ‘lifer’ this trip, and was desperate to find C. wiroti - my most desired species in Thailand full stop.

Despite my bad back from the night before, we hit the forest come 7pm and split off in groups of 2. Harry quickly spotted a cute little Malayan bridle snake (Lycodon subannulatus), as well as 3 Ahaetulla mycterizans and a Xenochrophis trianguligerus. Some interesting lizard finds included a large Bell’s angle-headed lizard (Gonocephalus bellii), a juvenile Cyrtodactylus consobrinus, and an adult Great angle-headed lizard (Gonocephalus grandis), one of the most impressive lizards in the country.

Malayan bridle snake (Lycodon subannulatus)

Triangle keelback (Xenochrophis trianguligerus)

Malayan-vine snake (Ahaetulla mycterizans)

Bell's angle-headed lizard (Gonocephalus bellii)

Juvenile Peter's bent-toed gecko (Cyrtodactylus consobrinus)

Great angle-headed lizard (Gonocephalus grandis)

It took me a while to find my first snake, but it was only a Malayan krait (Bungarus candidus agg.) which we left in-situ.

Malayan krait (Bungarus candidus agg.) in-situ

After this, the pain in my back got so bad that I had to stop herping and rest for almost 2 hours. David was also struggling to turn up snakes this evening, only finding a Pareas margaritophorus on the road.

Not willing to let our ‘final night’ end on a low, I plucked up the courage to get back out and hike streams with Harry. I further laboured to find snakes, only encountering a subadult Lycodon subcinctus and a sleeping Dendrelaphis formosus myself. Harry was having difficulty too, only finding one snake. However, the sole snake he found was a wonderful scarce wolf snake (Lycodon effraenis), a very uncommon species (as the name implies) and my favourite Lycodon in Thailand.

Malayan banded wolf snake (Lycodon subcinctus)

Scarce/brown wolf snake (Lycodon effraenis)

The following morning, Harry and I woke up early with the mindset of packing our things and leaving. However, there was a burning feeling inside me which begged not to leave this place. Harry and I discussed the situation and agreed that we both felt so close to finding C. wiroti - a completely baseless feeling of course, but something about this day had the presentiment of fate, a subtle murmuring of destiny. It simply did not feel right to leave. Once David awoke, despite wanting to go to the swamps all trip, he was in full agreement with our idea to sacrifice the swamps for another gruelling night of wet shoes and leaches. Henceforth, we strategised our night’s activities with precision.

We decided to stick to where had been statistically most productive (species-wise), and also within the area where we know C. wiroti has been observed. Harry had discovered a new network of streams the previous night, as well as a great new access point for them. We would start there and make our way up through the forest until we reached the T. sumatranus location, just past which we would meet our trails and explore them to the fullest. Narathiwat is too remote and difficult to return to anytime soon, this was do or die.

We hit the forest with a vengeance, full of commitment, determination, and focus. Any pain in my back, ticks, or leach invasion was negligible next to my focus on the task at hand. The night started quickly with a Hypsiscopus cf. plumbea on the path down to our access point. Minutes after reaching the forest, we got an adult Boiga bengkuluensis and a sleeping Ahaetulla mycterizans. Despite hearing their calls around our accommodation, David finally got our first photo of a giant green-eyed gecko (Gekko hulk), a newly described species.

Bengkulu cat snake (Boiga bengkuluensis) adult

Juvenile giant green-eyed gecko (Gekko hulk)

The next snake was our first reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus) of the trip, found digesting a large meal. These aren’t as common in far southern tropical forests as they are in other parts of Thailand, but considering the amount of stream walking we’d done, it was long overdue. Harry soon spotted another snake, our third Malayan krait (Bungarus candidus agg.) of the trip, and by far the largest. These seem to be the dominant Bungarus in the area, which is surprising considering Bungarus flaviceps tends to occupy the forest stream niche in most other tropical dipterocarp forests in Southern Thailand.

Reticulated python (Malayopython reticulatus)

Malayan krait (Bungarus candidus agg.)

This was shortly followed up by a Malayan flat-shelled turtle (Notochelys platynota) and a Hagen’s pit viper (Trimeresurus hageni), only a couple feet away from each other.

Malayan flat-shelled turtle (Notochelys platynota)

Hagen's pit-viper (Trimeresurus hageni)

Again, not long after, we finally got the last extant Boiga species in the area, a beautiful dark-headed cat snake (Boiga nigriceps). A species we often talk down upon for being overrated and common, but this one was exceptional. It was also the final species of Boiga which Harry had to see in Thailand. There was a Pareas carinatus in a tree a few meters from where we found the Boiga.

Dark-headed cat snake (Boiga nigriceps)

The next find of the night was very interesting. I poked my torch round the roots of a large tree next to the rocky bank, and saw the face of Bengkulu cat snake (Boiga bengkuluensis) staring back. Upon closer inspection, I realised that it had over two thirds of its body inside an arboreal termite nest. I was confused for a second, until I remembered that other members of the genus have been recorded laying their eggs inside arboreal termite nests. We had no confirmation, but this is almost certainly what was occurring here. Funnily, I called the guys over and Harry spotted a juvenile Boiga bengkuluensis resting in a sapling right above where the adult laying eggs was. We made a mental note to return to this spot later and moved on.

Bengkulu cat snake (Boiga bengkuluensis) 'laying eggs' in a termite nest

Subadult Boiga bengkuluensis

After progressing past the Trimeresurus sumatranus spot from earlier on the trip, we reached the trails we’d consistently visited on every night in the area so far. I had been going as hard as possible for C. wiroti all night and was beginning to get discouraged. Tons of other snakes, but not our target - same as usual. David was not far from me on the trail, and he had stopped moving, so I walked up to see if he had found something. The second I reached him, something was not normal, something about his body language seemed way too happy. He was trying to act normal but I could see this glimmer in his eyes which his casual attitude failed to belie. He then got his video camera out and said “somewhere around you is the biggest female wiroti you will ever see.”

Sure enough, sitting on a fallen branch on the edge of the trail we’d walked every single night thus far was an absolutely giant Wirot’s pit-viper (Craspedocephalus wiroti), so fat it looked almost comical on the flimsy twigs, and completely unbelievable. I simply couldn’t wrap my head around what we had found. Why was it there? Why was it so big? Is this even real? Not just ‘my’, but our number 1 target species in Thailand was just basking in all its glory in the most painfully obvious place you could imagine. This species is supposed to sit high in trees, perfectly camouflaged against large branches. What was it doing here? Arguably the most incredible aspect of this entire story is how David spotted it. He had stopped walking to remove a large leach crawling up his shoe, and as he bent down he brushed against the fallen branch and saw a flash of white from the corner of his eye. Expecting it to be a frog hopping away, he had looked up and seen the C. wiroti striking at him. I could ramble about this snake and this moment forever, but I’ll stop talking and let the pictures speak for themselves.

Hands-on with the Craspedocephalus wiroti

Wirot's pit-viper (Craspedocephalus wiroti) striking

Craspedocephalus wiroti

Craspedocephalus wiroti

It wasn’t even midnight by the time we had found the C. wiroti. This had been the most productive night by far given how much we’d seen in the short amount of time, but the sheer relief and adrenaline rush this showstopper had brought on had left us weary of herping further. Somehow, we still found more snakes. On the way to the car to grab our camera gear, Harry spotted a male Wagler’s pit-viper (Tropidolaemus wagleri), and on my way to put my camera gear back in the car, I encountered a truly huge Boiga bengkuluensis crossing the path in front of me. Snakes were active tonight.

Male Wagler's pit-viper (Tropidolaemus wagleri)

Bengkulu cat snake (Boiga bengkuluensis)

By the time we were done with the C. wiroti, we felt more like celebrating than herping. However, Harry and I had a great interest in investigating the Boiga bengkuluensis ‘laying eggs’ further, and so we decided to hike back down the stream and see what was going on. By the time we arrived at the large tree, both Boiga bengkuluensis were gone. Harry got to work taking pictures of the termites and their nest for data purposes, while I shone my torch around the other nooks and crannies of the termite nest and tree roots for anything of interest. Within a small crevice, I saw something pinkish-red. I assumed it would just be some plastic trash, as I had been momentarily thrown by red and blue plastic wrapping countless times on this trip already. However, upon closer inspection, I noticed it was black with a pale blue stripe on the side, and the reality dawned on me that we had done what I thought was impossible.

Malaysian blue coral snake (Calliophis bivirgata flaviceps) in-situ

Tucked in a crack between the termite nest and the tree buttress was our third and final key target species, the Malaysian blue coral snake (Calliophis bivirgata flaviceps), a sight which still beggars belief to this day. Finding one out moving during the day (or night) is hard enough, but discovering one tucked in a crevice is beyond crazy. To think of all the cracks and crevices I searched during this trip, and the only snake I got within them was this… it’s insane. Anyway, Fortunately for us, there whereas no holes from it to flee down and we removed it from the crevice by gently poking its tail with a twig, and soon got to see it in all its glory. The downside of this find was that it was in the process of shedding when we caught it. David and Harry thought it was too early to manually shed it, but the snake actually almost entirely shed itself in the time we held onto it for photos. My best images were from before it finished the shedding process, but David managed to get some when it was complete.

Malaysian blue coral snake (Calliophis bivirgata flaviceps)

Malaysian blue coral snake (Calliophis bivirgata flaviceps)

So there you have it, that blue coral was the final snake of the night, a night which undoubtedly surpassed all others as the best herping ‘day’ of my life - and I’ve had some good ones in the past. It may have had absolutely nothing to do with those gut feelings we had on the final morning, but I know I’ll be entertaining abstract ideas of fate and destiny for a while.

The trip was not over, however. The following day, on the drive out of village, we saw another Malayan racer (Coelognathus flavolineatus) crossing the road. Then, after another unnecessarily long journey out of the Deep South, we arrived at our layover location. The entire group was shattered from the toil of the previous 7 days, but I wanted to squeeze the last juices out of the south’s biodiversity, so we headed back out for a couple of hours. We got a western mangrove cat snake (Boiga melanota), a Martaban mud snake (Homalopsis semizonata), a Bengkulu cat snake (Boiga bengkuluensis), and a large white-spotted cat snake (Boiga drapiezii) - such a typical Southern Thailand Boiga-fest. Another interesting observation was this amplexus pair of giant river toads (Phrynoidis asper).

Western mangrove cat snake (Boiga melanota)

Martaban mud snake (Homalopsis semizonata)

Giant river toad (Phrynoidis asper)

White-spotted cat snake (Boiga drapiezii)

Including 3 unidentified snakes seen crossing roads, we saw a staggering 92 individual snakes in 8 nights, comprising an incomprehensible 34 species. Narathiwat went above and beyond our wildest dreams, blowing our lofty expectations out of the water. Still, with so much yet to discover in this largely unexplored area, I’m sure we’ll be back.

Complete Species List of the trip:

*Note: Species may appear in this list but not the above report if individuals were not photographed or observations were fleeting.

Snakes:

Ahaetulla mycterizans x7

Ahaetulla prasina

Aplopeltura boa x3

Boiga bengkuluensis x9

Boiga cynodon

Boiga drapiezii x3

Boiga jaspidea x3

Boiga melanota x2

Boiga nigriceps

Bungarus candidus agg. x3

Calamaria schlegeli

Calliophis bivirgata flaviceps

Calloselasma rhodostoma

Coelognathus flavolineatus x2

Craspedocephalus wiroti

Dendrelaphis formosus x3

Elaphe taeniurus ridleyi

Homalopsis semizonata

Hypsiscopus cf. plumbea x3

Lycodon albofuscus

Lycodon effraenis

Lycodon subannulatus

Lycodon subcinctus x3

Malayopython reticulatus

Oligodon signatus

Pareas carinatus x4

Pareas margaritophorus agg. x4

Ptyas fusca x2

Ptyas korros

Trimeresurus hageni x11

Trimeresurus sumatranus

Tropidolaemus wagleri x2

Xenochrophis trianguligerus x2

Xenopeltis unicolor x6

Lizards:

Aphaniotis fusca

Calotes emma

Calotes versicolor

Cyrtodactylus bintangrendah

Cyrtodactylus consobrinus

Cyrtodactylus lekaguli

Cyrtodactylus quadrivirgatus

Draco sumatranus

Eutropis longicaudata

Eutropis multifasciata

Eutropis rufigera

Gekko browni

Gekko hulk

Gekko monarchus

Gonocephalus abbotti

Gonocephalus bellii

Gonocephalus grandis

Gonocephalus liogaster

Lygosoma cf. siamensis

Takydromus sexlineatus

Varanus nebulosus

Turtles:

Notochelys platynotan

Amphibians:

Amolops larutensis

Chalcorana eschatia

Chalcorana labialis

Fejervarya cancrivora

Hylarana erythraea

Ingerophrynus parvus

Leptobrachium hendricksoni

Leptobrachium smithi

Leptobrachella eos

Limnonectes blythii

Megophrys nasuta (calls only)

Odorrana hosii agg.

Phrynoidis asper

Polypedates leucomystax

Zhangixalus prominanus

Pulchrarana signata