Part 1: The Backstory

Recently, the Explore Herpetology team published the most significant discovery from our three years of operations in South-East Asia. Our most notable previous publications were the discovery of the ultra-rare and charismatic Peninsula supple skink (Lygosoma peninsulare) in Thailand, and of course the description of the cave kukri snake (Oligodon speleoserpens) from Satun and Trang provinces, also in Thailand. However, this recent new species blows these out of the water in terms of significance and novelty.

First of all, we must highlight an important distinction when it comes to the discovery of ‘new species’ in South-East Asia. While there are multiple new Crotalinae (pit viper) species from South-East Asia and China published every year, this does not mean that there is an unlimited treasure-trove of never-before-seen species of pit viper waiting to be found there. The vast majority of these new descriptions are what we refer to as “splits”, typically when a wide-ranging species of pit viper (take for example Trimeresurus macrops or Ovophis monticola) is actually a ‘complex’ of morphologically similar but genetically distinct species due to evolutionary isolation. Most of these ‘new species’ populations would have been known of and documented for a long time – just referred to as the nominate or ‘cf.’ (compared to) the nominate species. Only when mitochondrial DNA of these isolated populations were compared to that of the ‘type’ (first-described) population was significant genetic divergence revealed, leading to their description as a new species. Trimeresurus kraensis, Trimeresurus cyanolabris (both Idiiatullina et al. 2024) and Trimeresurus cryptographicus (Pawangkhanant et al. 2025) are recent examples of this. While these new species descriptions are valuable and we support this work, it is very different to when you take a first look at an animal and immediately know it is new and drastically distinct to any currently described species. Encounters like this are becoming increasingly rare as more of South-East Asia is explored and surveyed.

If you had asked experts if there were any totally novel Protobothrops species waiting to be discovered in South-East Asia in early 2023, many (including myself) would have answered ‘probably not’. Protobothrops is a small genus in comparison to Trimeresurus and Oligodon, which see new species descriptions on a frequent basis. Protobothrops is also comprised of larger-bodied pit vipers which are typically very distinct from their congeners, making them easier to detect, describe and much higher profile targets for researchers hungry for new species publications. In modern colloquial terms, they have more ‘clout’. For many, Protobothrops kelomohy (Sumontha et al. 2020) may have felt like it was the last (non-split) Protobothrops left to be discovered. Despite reaching close to 150 centimetres in length, P. kelomohy was shrouded for decades in the most remote region of Thailand, with its low population density and secretive ecology adding to the challenge of finding it. However, the discovery of P. kelomohy begged the question ‘could there be others like this?’.

We finally got an answer to this question in May 2023, when Riley Fraser sent me blurry images of a strange lance-headed pit viper from a cave in Vang Vieng district, Laos, right after they were posted online for identification by P. L. Stenger. The snake was identified at the time as Protobothrops sieverosorum – another troglophile crotaline snake known from Laos. I forwarded the link to my colleagues Parinya Pawangkhanant and David Fröhlich, who both immediately confirmed that this was an incredibly significant image; the very first ever image of a brand new Protobopthrops species. The images were shared more widely amongst our collaborators, and the hunt was on.

The first images of the undescribed Protobothrops species.

The first images of the undescribed Protobothrops species.

The first images of the undescribed Protobothrops species.

What was fascinating about this particular observation, on top of it being a clearly new Protobothrops species, was that the area it was observed at was nowhere near as remote as where Protobothrops kelomohy occurs. Laos is a very poorly explored and rarely travelled nation in comparison to neighbouring South-East Asian states, but Vang Vieng district is arguably the most popular tourist destination in the country and had been surveyed by herpetologists several times in the past, leading to the description of micro-endemic species such as Lycodon davidi (Vogel et al. 2012) and Cyrtodactylus pageli (Schneider et al. 2011). The towering limestone karst formations also make Vang Vieng one of the most popular destinations for caving/spelunking in South-East Asia, with hundreds of people visiting both easily accessible and remote caves every day.

It was this particular draw (caving) which led to the first ever documentations of this unknown snake. In November 2023, yet another set of photos of this unknown species were posted on the internet – also by a tourist exploring a cave near Vang Vieng during the daytime. These images were much clearer than the original set and alerted many more people to the existence of this undoubtedly undescribed species. Hereby, efforts to find the species were ramped up even further, both by our friends/colleagues and other groups/individuals. After this second observation, it was winter in Laos, so these expeditions were all as unsuccessful as previous surveys.

I first made my way out to survey Vang Vieng in late March – early April 2024, along with David Fröhlich and Plato Stefanopolous. We warmed up targeting limestone karst-dwelling Protobothrops and Trimeresurus species in Khammouane province, before moving on to the main event in Vang Vieng district and linking up with Peter Brakels’s team. We covered a huge amount of ground during our four nights in the area, but came up empty handed. However, it was on this trip where potentially the most valuable piece of information was uncovered.

During a conversation about the unknown pit viper with local Hmong villagers (translated from the local language by Peter’s friend Ked), they informed us that they almost never saw our target species, what they call the “big mouth snake”, in caves. Caves had been the primary microhabitat we had been targeting during our team’s collective expeditions. On the contrary, they most frequently observed what they considered a “very rare snake” along streams at the base of limestone karst formations, especially at the end of the rainy season in October/November. Without photographic evidence, their words were unreliable, but it certainly made us think twice about how to conduct our search effort.

After the third sighting of the unknown Protobothrops species was shared privately with us just one month later (in early May 2024), also by a tourist exploring caves near Vang Vieng, it was hard to dismiss the idea that this was a troglophile species. All three observations known of this new species were from within caves. It would not make sense to overlook this raw data. However, my theory was that there is a clear survey bias due to the hundreds of spelunkers entering limestone karst caves every day with flashlights. I believed that the snake may not have an overt preference for entering caves. It was just a statistical probability that the very few individuals which did stray into caves, while hunting or looking for a place to rest during the daytime, would be sighted and photographed by the many tourists exploring the caves, eager to document what they saw inside. I believed in the villagers’ observations; the failures of many different researchers to find a single individual within caves across many trips suggested that a change in strategy was desperately needed. Hereby, I marked a specific week in late October 2024 during which I would return to Vang Vieng and search for this species no matter what.

The second observation of the new Protobothrops species.

The second observation of the new Protobothrops species.

The third observation of the new Protobothrops species.

Rupert, David, Peter & Plato in Vang Vieng.

Part 2: The Capture

Come late October, I arrived in Laos with the plan that my 5 nights in Vang Vieng would be spent focusing on limestone karst valleys, while daytimes would be dedicated firstly to exploring the three caves where the snake had been sighted, then other caves in places I projected the species to also occur. Fortunately for me, I did not need to invest any of the energy necessary to climb swelteringly hot limestone karst formations in the daytime to access caves, as the first night exceeded any expectations I had about what could transpire.

Protobothrops had long been one my absolute favourite genus of snake in South-East Asia, with so many incredible representatives. Species such as the magnificent Mangshan pit viper (Protobothrops mangshanensis) or the incredibly elusive Omkoi lance-headed pit viper (Protobothrops kelomohy) mentioned previously. The latter has caused me much grief over the years, as I have been to its remote range in Thailand on four separate field trips without finding a single live individual. The prospect of discovering a new species within my favourite genus, combined with the frustration from my failures with Protobothrops kelomohy, created a burning desire to find the unknown crotalid occurring in Vang Vieng, which seemed to be morphologically closest to P. kelomohy than any other congener.

One of the most captivating and addictive aspects of searching for wildlife is the moment when your ambitions are realised. If you take it as seriously as I do (which means your entire body and mind is committed to accomplishing your goal), you spend every minute you are out searching or resting at the hotel visualising scenarios and imagining the moment when you finally see your target. It is all you think about, and after several hours or several days it can start to feel like an impossible goal – a pipe dream, a fantasy. Emotions can hinge on fragile probabilities, and destiny can be impacted by split second decisions such as ‘do I take that trail, or this one?’.

Therefore, it felt absolutely surreal when, almost three hours into my search on the very first night and deep into a limestone karst stream valley, I glimpsed a tiny movement atop a rock out of the corner of my eye. I had been scanning the limestone karst rocks closer to the cliff face, but this movement was on one of the many large boulders strewn near the dry streambed. I locked in on it and within a millisecond it was obvious what I was looking at - it was the tail of the undescribed Protobothrops. I slowly crept round the rock as carefully as possible, so as to not to disturb it. It noticed me after a moment and lifted its head up towards me, which was when I took the first photo with my phone. Seeing everything I had been dreaming of materialise in front of me is a moment I will never forget. However, I was now faced with the moment I was most afraid of; catching the snake without it escaping or getting bitten.

The exact type locality for the new Protobothrops.

In-situ phone image of the new Protobothrops.

Anyone who has handled small and slender Protobothrops species will understand how difficult they are. Not only will they never stay on a snake hook for a second, but they are fast-moving and incredibly jumpy with a shockingly rapid strike they are absolutely not shy of showing. Furthermore, the environment I found this snake in was also extremely treacherous, probably the worst area possible. Nothing but rocks everywhere, small and large, with seemingly innumerable crevices and holes which each provided a traumatising premonition of the snake disappearing. This not only made my movement difficult, but I also had to be so precise with where I moved the snake to. I identified an area a couple metres away on the streambed where there was an open space with some sand and small rocks, got all my equipment out of my bag so it was ready when I needed it, then moved in with the aim of getting the snake there as fast as possible.

It is hard to remember exactly how this situation played out, but I can remember that my heart was in my mouth as the snake immediately sprung into life and fired several lightning-fast strikes in my direction as I closed in on it with my snake hook. I immediately noticed huge white-sheathed fangs at full extension every time it opened its mouth. With some difficulty, I got the snake close to the open area, but it dropped onto the ground and shuffled itself under a rock within seconds. For a moment, I genuinely thought that it might be gone for good, but fortunately the rock crevice was a dead end and it was trapped. Getting it out was not easy, but I utilised a combination of my hook and hand to get it out and used every bit of my experience handling and capturing venomous snakes to get it secured quickly. Mission accomplished, with no bites.

I immediately brought the snake back to my hotel and set up a safe and secure photography set using some limestone rocks which had been cast aside by a construction project nearby. This was my very first opportunity to look closely at the snake, which was fascinating to observe in the flesh after what we had seen on the low-quality images shared online. It indeed did closely resemble Protobothrops kelomohy in terms of body proportions and the dorsal zig-zag patterning, but was clearly distinguished by a yellow snout and yellow tail, with yellow streaks on the dorsal surface of the head, as well as very different patterning on the labial scales and a pale brown base colour. An attractive colouration, fresh out of shed without a single blemish or injury, but this was irrelevant to me. The significance of this find made it mind-blowingly beautiful regardless of how it appeared.

Huge fangs.

Full body image.

Yellow and black patterning on the head.

Full body image.

Yellow snout.

Yellow tail.

Part 3: The Process

As soon as the snake was captured, I contacted Peter Brakels, who alerted Dr Saly Sitthivong about the capture, who came brought the snake back to Vientiane. It was then brought to Nathanaël Maury who possessed all the equipment necessary for Dr Saly to process and sample the specimen. We took every measurement and scale count, determined the sex of the snake, and took samples of the scales, blood, heart and liver tissue for DNA analysis. This individual was a female, presumably a young adult, measuring 82.5 centimetres in total length. We also photographed the snake at all angles in white background.

From there, we discussed how to proceed and get the description published as fast as possible. Professor Nick Poyarkov was by far the most experienced of our frequent collaborators in South-East Asia, and had recently executed a similar fast-tracked project for the description of Laodracon carsticola (Sitthivong et al. 2023) in collaboration with the National University of Laos. Therefore, Dr Poyarkov took charge of structuring, overseeing and assigning tasks to make the process as professional and effective as possible – with the aim of getting the paper published within four months.

I suggested five name ideas for the species, and within days we had agreed upon a binomial for the new species; Protobothrops “flavirostris” – the specific name referring to the yellow snout visible in both our specimen and in the clearest images of one of the cave-dwelling individuals photographed prior. We began the writing immediately afterwards, with Dr Tan Nguyen drafting the base manuscript for the paper and entering all the morphological measurements provided in a spreadsheet by Nathanaël and myself. Sabira Idiiatullina and Dr Poyarkov handled the genetic sequencing through their laboratory at Moscow University, then wrote all the sections covering the genetics, such as the phylogenetic tree and systematics. I led the writing of all remaining sections of the paper, with important contributions from Peter Brakels, Saly Sitthivong and the other co-authors. When we had added everything necessary, I handed over the final draft to Dr Poyarkov, who reviewed and edited everything to a very high standard.

We submitted the finished paper to the trusted journal Herpetozoa, which has a short turnover window on publications. The team had to make some small amendments once the first review came back, but after that it was cleared to go. On the 25th of February 2025, just three months and four days since the type specimen was captured, “A new endemic karst-associated species of lance-headed pit viper (Squamata, Viperidae, Protobothrops) from Laos” by Grassby-Lewis et al. was published.

Nathanaël Maury photographing the new Protobothrops.

Images by Rupert GL & Nathanaël Maury.

Taking measurements.

Published.

Part 4: The Future

When writing a paper, we are restricted by the scientific writing style in how much we can speculate and guess. We are bound to formulate clear and concise analysis based on evidence only. Hereby, in this final part of my very un-scientific article, I will extrapolate on our thoughts stated within the paper and provide additional speculation on the ecology, population and conservation status of Protobothrops flavirostris.

If it was not evident already, Protobothrops flavirostris is extremely rare. By “rare”, I mean “not occurring often” – probably due to a combination of low detectability and low population density. Zero public records or images before 2023 speaks volumes. The local villagers further corroborated this theory by stating that they seldom encounter this snake, despite living amongst the snake’s limestone karst habitat and hunting in the forest regularly – often at night. Furthermore, it took many expeditions led by highly experienced hobbyists and professional herpetologists to capture just one individual of the highly sought-after serpent, suggesting that even trained eyes with experience detecting cryptic snakes will struggle to uncover this species. This is extremely akin to its closest relative (genetically and morphologically), the ‘Omkoi lancehead’ (Protobothrops kelomohy), which has not been captured once by a naturalist since the type series was collected by mountain village hunters and Ton Smits. It was also known of for many years before a live individual was captured, taking countless field trips to acquire a single specimen. Whether this shared rarity is a product of the natural ecology of these two species, or additionally affected by external factors, is up for debate.

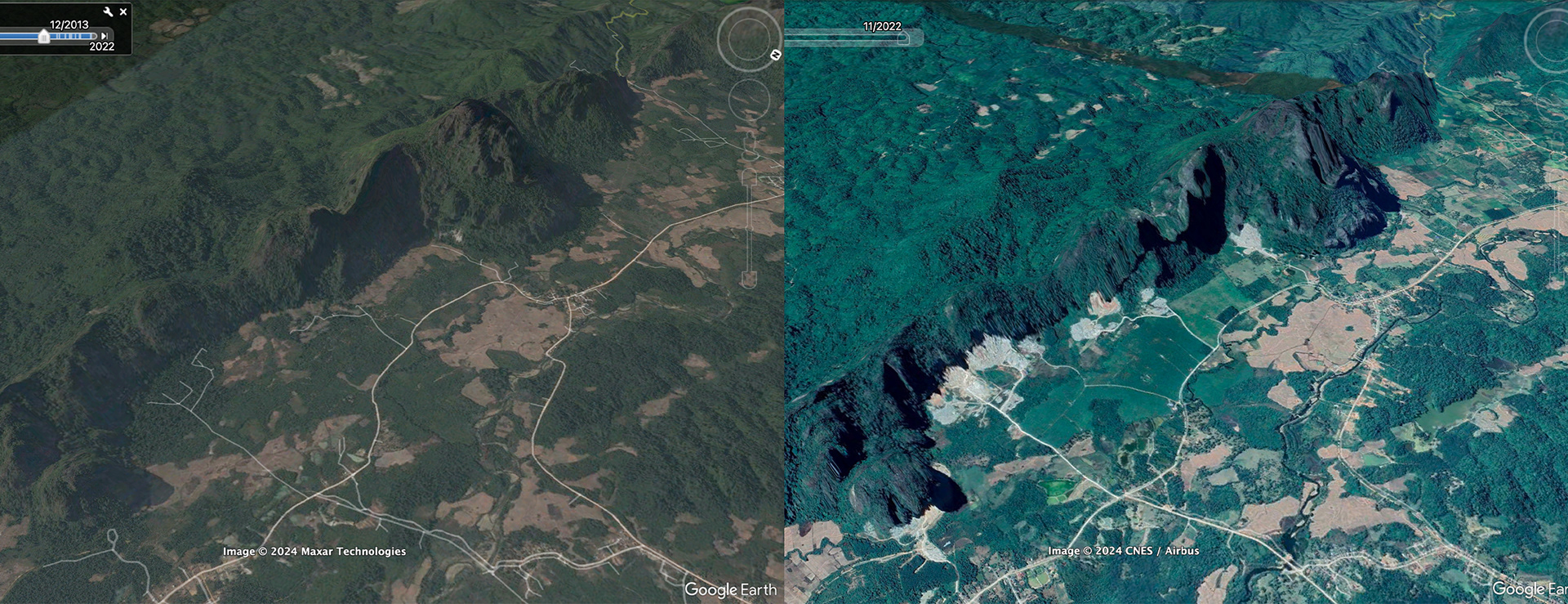

There is no doubt that the habitat for both Protobothrops kelomohy and Protobothrops flavirostris is severely degraded. In Vang Vieng, swidden agriculture commonly wipes out swathes of high-quality forest, while industrial mining of limestone karst formations for lime and rare ores has also led to significant habitat destruction in the area. It is likely that this affects the species’ density in the areas which are more easily accessible to humans, making it harder to observe. As mentioned in the paper, cave ecosystems are decimated in Vang Vieng, leading to an almost complete loss of bats and other key fauna from within most accessible cave systems. It is likely that the healthiest populations of this species are restricted to almost inaccessible karst valleys and to caves with healthy ecosystems and high humidity. Hereby, it is possible that all the individuals observed so far were outliers who strayed into areas they do not typically inhabit in good numbers.

Vang Vieng limestone karst massif.

Mining degradation of limestone karst formations in Vang Vieng.

That said, three citizen observations of Protobothrops flavirostris from within caves in a single year opens the door to more speculation. We have previously discussed how the high numbers of cavers visiting Vang Vieng creates a survey bias for the species in that specific microhabitat, but it does not explain why there were no records of the species prior to 2023. A potential theory explaining this phenomenon could be the absence of tourism during the Covid travel restriction years between 2020 – 2023. This period saw drastically lower numbers of tourism to Laos, and may have allowed somewhat of a ‘regeneration’ of certain cave ecosystems which had been frequented by tourists but rarely accessed by local hunters. When tourism returned in accelerated numbers from 2023 onwards, there was a legacy of Protobothrops flavirostris individuals entering less-disturbed caves to hunt or rest and were easily observed by keen-eyed spelunkers.

It is also probable that this species is highly seasonal, with a spike of activity in early May (two records) and late October-early November (also two records). This is comparable to the historical records of its closest congener, Protobothrops kelomohy, for which records are also heavily biased towards early May and late rainy season (October - November). The majority of surveys aiming to find Protobothrops flavirostris were not carried out during these times of the year. If there had been a more dedicated search effort in May and October, it might have taken less time to detect a single specimen. It only took me one single trip in October to find an individual, although it is worth noting that I spent a further four nights searching at the site I found P. flavirostris, and failed to locate another individual. This indicates that even during the prime activity seasons, P. flavirostris are still rare and possibly dependent on specific weather conditions. The day I found the type specimen was hot and dry, while the following four days were all stormy with rain in the late afternoon/early evening. Of course, it is also entirely possible that its dorsally compressed head and slender body, is a strong indicator of a highly cryptic and secretive lifestyle - evolved for crawling within narrow rock crevices. This may well be the defining factor above all else as to why it has been so rarely sighted throughout its existence.

For Protobothrops flavirostris, this does not mean the habitat destruction and disturbances affecting the area will not be consequential for the population of the species. We do not have any real understanding of its habitat preference or range. Just as it could be distributed much wider than we are currently aware, it could equally be restricted to only the karst massif around Vang Vieng city. The karst habitat around Vang Vieng is not protected and is under constant threat from human development, mining operations and unsustainable farming practices. Moreover, the Hmong villagers we spoke to reported that the snake has become significantly rarer in in the last 10-15 years, a worrying trend. This underlines the need for further data on this species.

Hereby, we call on the greater community of naturalists to aid us in our quest for more information about this elusive species. If you find yourself in or nearby Laos, make a stop in Vang Vieng and use the data presented in both the paper and this article to try and observe an individual. In the very fortunate event that you find a live or dead individual in the wild, please contact myself or one of the other authors immediately. Additionally, take note of all relevant information. Take coordinates, pictures of the snake and the habitat it was found in, write the time, date and as much environmental data as possible.

While it may seem at times like every mountain has been summitted and every species seen already, the discovery of Protobothrops flavirostris should highlight how much there is to be uncovered in South-East Asia. If a large-bodied pit viper like this can stay hidden until 2023 while occurring in a populated area, then evade capture for a further year and a half, what else is waiting to be discovered within the caves, karst valleys and misty mountain peaks of the region? Only time will tell, but there has never been a better time to get out there and find out for yourself.

Interested in joining an expedition to remote corners of South-East Asia with potential for new species discoveries and more? Plan an expedition with Explore Herpetology today.

Protobothrops flavirostris.

The entrance to Vang Vieng.

Protobothrops flavirostris.